Rick Myers: Two Things, Quite Intertwined

I first met Rick Myers a few years ago at the Multiple Formats Art Book Fair in Boston. I had picked up his 2017 book A Bullet for Buñuel: Fragments of a Failed Bullet some years earlier and was intrigued by its absurd and circuitous attempts to recreate the bullet mentioned in an anecdote told about the filmmaker Luis Buñuel. When we met at the fair, I was delighted to learn more about his extensive output, which shared a similar spirit of thoughtfulness and sense of humor to the Buñuel project, all set off by his keen sensibility of presentation, alternating between a grainy DIY-ness and a gravitas-lending formal elegance. When I saw him at the 2025 edition of the fair this past March, he mentioned the opening of Caesura Unit, a gallery, book, and performance space he’s co-organizing in Easthampton Massachusetts, where he is based. We sat down recently to discuss his vision for Caesura Unit, as well as art, life, and things in between.

Ben DuVall

___

Ben DuVall (BD): Let’s start at the beginning—I’m curious to know about the beginnings of your art practice and how you came to be in Western Mass?

Rick Myers (RM): Those two things are quite intertwined, I grew up in Manchester but my wife is originally from Western Mass. She’d lived in Manchester before I knew her and we met at an event to mark the anniversary of [Joy Division’s manager and Factory Records co-founder] Rob Gretton’s passing. My friend’s band was playing in his honour, they’d released records with Rob’s label and I’d made their sleeve artwork since the beginning. Rob was really supportive of me making record sleeves and videos, and he’d bought me my first computer to help me do that work. Meeting that evening became a long-distance relationship between Manchester and Western Mass. When I started visiting here, it was an amazing time and place that was really idyllic, culturally rich, and non-cynical in a way that was completely refreshing after living in Manchester all of my life. There was a really incredible and supportive music situation happening and I made lifelong friends. I eventually moved here, and now it’s just an amazing place for our daughter to grow up, so this area made sense at first, then all over again in a different but still really related way.

BD: Then when did the idea for Caesura Unit come about and what was the impetus for that?

RM: It grew out of an ongoing conversation with Guy Pettit. He ran a non-profit art space in Western Mass called Flying Object that was really active when I first came here. Guy invited me to do a show of collaborative work made with with Ben Estes and Kim Gordon, followed by a solo show. Guy and I have talked for years, he closed Flying Object and moved to LA, then lived in New York for a while, and gravitated back to Western Mass just before Covid hit. We were hanging out in his garage occasionally around that time—which is actually a really nicely finished space, as is always the case with Guy—talking about ideas of how we could get people together, and the project grew out of that conversation. We talked briefly about his garage being a space for programming, then the idea of my cabin-studio in Easthampton, MA becoming a gallery, but decided to look for a space and co-founded the gallery, with the help of another friend, Matt Dube, who is now Caesura Unit director of operations.

BD: From what I've seen of the current show and the events so far, it’s a great mixture of visual art, poetry, people who are working with words and people who are working with sound, and books, and more. I wonder if you can sum up your philosophy of what will be going on in the space, or what your ideal for it is.

RM: The first show is called Bad Line, it’s a group show I curated that formed out of research interests in my own practice, threaded together with conversations over many years. This felt like the right starting point to try and show connections between a group of people, expanding ongoing dialogues and developing language around threads through the work. I wrote a short statement on the notion of the “bad line” and asked James Hoff, Matthew Higgs, Haein Song, Sergej Vutuc, Sam Winston, Arthur Fournier, Alice Centamore, Roy Claire Potter, Anaïs Ngbanzo, Demdike Stare, Xylor Jane, and Steven Zultanski, to be part of the project. Also Christian Marclay, who I’d not been in touch with before, kindly gave permission to include a seminal piece of his that I love, which fit perfectly with the bad line. It turns out it was one of his favorite pieces as well, Record Without a Cover.

An artist talk opened the exhibition with James Hoff, Haein Song, Sam Winston. Then an event with the first reading of a poem written for the project by Peter Gizzi, and live musical improvisations in response to the exhibition by Matt Krefting, Wednesday Knudsen and Christoph Heemann. A film screening of lesser-seen Luther Price super 8mm films took place at the closing reception, programmed by Josh Guilford, an incredible film academic I met when he screened Paul Sharits 16mm films, and we’ve been friends ever since. There will be a reprise of Bad Line in September for a series of short-form plays for two performers, with one performer in the gallery, in conversation with a second performer audible in real time via a telephone call. So in terms of a philosophy or some kind of thread, I think it’s just the gravity of these people, their work, and research coalescing, and a way to expand conversations and build language around correspondences. I’ve worked on my own for decades, literally making work on my own in a room, and this felt like a chance to change my own patterns. I think the philosophy is actually just to enjoy it, it’s maybe that simple, just to really enjoy all these people and the threads between us.

I’ve been talking a lot with Arthur Fournier, who lent a formative Sarah Charlesworth photostat piece from 1977 for Bad Line care of Dickie Landry. Arthur is organizing an incredible exhibition at Caesura Unit which opens in October. When me and Arthur were talking about the Bad Line, where we came to is that, the rupture in the line exposes the space that was there before the line existed.

BD: Speaking of bad lines, one thing I love about your work is your interest in drawing in the broadest sense—mark making, drawing machines, impressions, and all of these things. Something that I have been thinking about for some time in my own work is how do you define drawing? Vis-a-vis painting, sure, but also as this immediate, thinking activity. I wonder, do you have a working definition of drawing that you like, that relates to what you’re doing?

RM: I think drawing is more of a source for thought and output than something I try and define. Just some natural default I keep coming back to that shifts in different ways. The residue of thought, or process, or objects moving from one place to another, a trajectory. In 2011 I made a piece with an infra-red eye-tracking study as a source of choreography for a figure skater on a black painted ice rink, the movement of eyes forming a performative drawing process. Over recent years I’ve been working with interruptions as systems for movement, based on the body integrating and operating within systems, so rather than the body facilitating drawing, systematization of movement outputs residual documents, methods of drawing moving the body.

Drawing with removed subject, 2011

Still image

BD: I was going through a bunch of your books and things from over the years and I came to the final chapter of A Bullet for Buñuel, which is called “Failed Drawing,” which maybe fits into that way of thinking.

RM: That project was built around an absurdly long-winded attempt to achieve failure. The impetus was a story told by Georges Sadoul, a French film critic and friend of Luis Buñuel. Sadoul explains that Buñuel had an interest in ballistics—he collected guns, and wanted to make a bullet with such a weak charge that when it was fired at him, it would slide harmlessly off his shirt. He worked on it for months, believed he’d made the bullet, went outside to test it, set up a target on phone books against his wall and fired the bullet. It went through the target, the books, the wall, and lodged in his neighbor’s wall. Sadoul is crying with laughter telling the tale summing up Buñuel, saying he puts very little into his films, but they explode. I don't suffer from that problem, so I endeavored for years to create the failure that Buñuel had been too powerful to achieve.

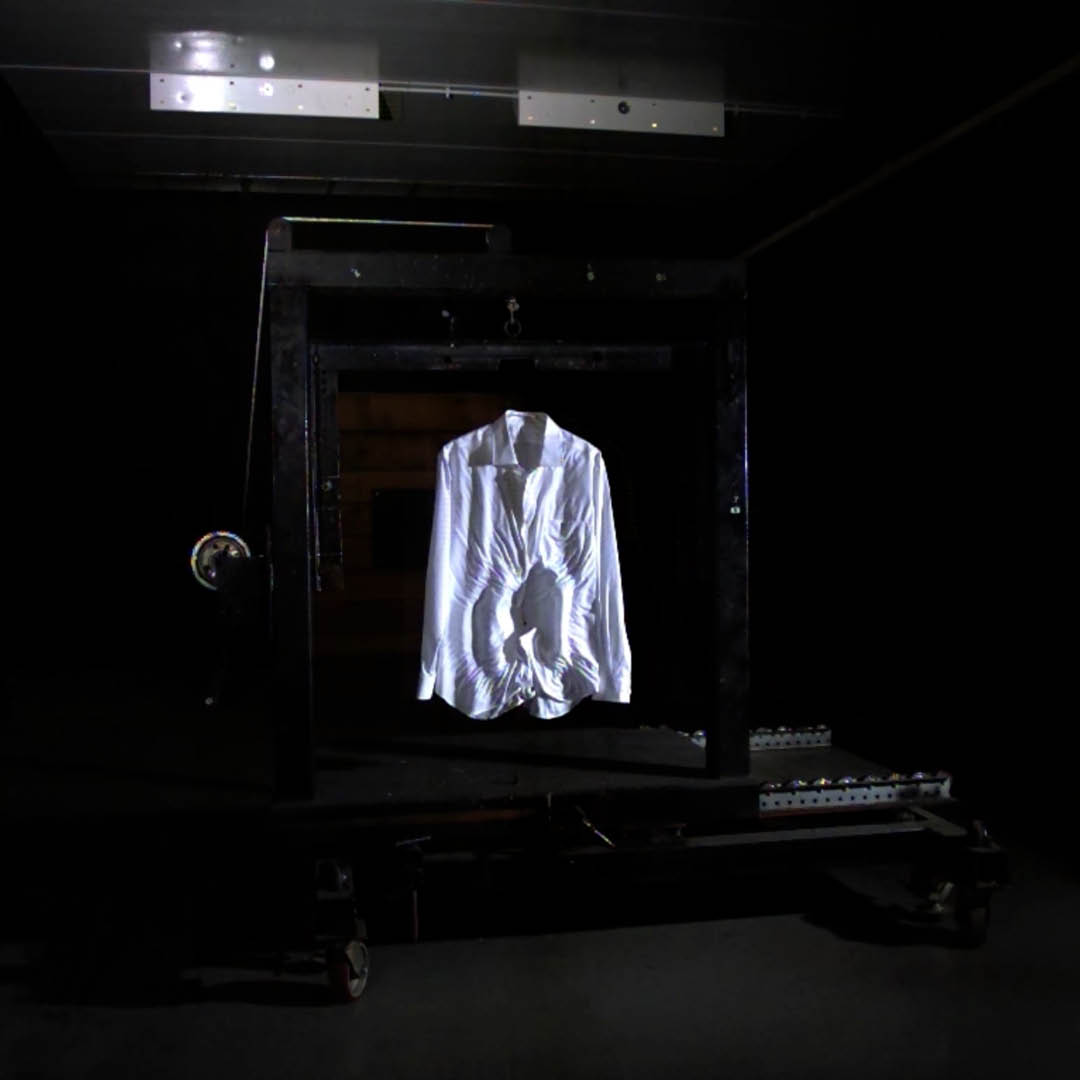

The notion of a failed drawing became part of this absurdly serious project. It involved trying to gain access to a US ballistics lab which tests for 30 global governments, negotiating a discounted artist rate for ballistics engineers to slow down a bullet, to use as a device to animate an exacting replica of a specific shirt worn by Buñuel, playfully interrupting very real things, intervening in mechanisms of violence to breathe life into an inanimate ghost-like effigy.

A Bullet for Buñuel: Failed Drawing, 2013

Still image

BD: In that book, and in much of your work, the mode of presentation is no small part of the piece. I think of your Bite Marks in Paper Archive, which is presented as this multi-volume archival box and then you open it up and it’s these beautifully presented little scraps of paper which are puzzling at first, and then you realize the concept, but I think the seriousness of the presentation, combined with the humor and absurdity is what makes the piece. Or like the episode of the hard drive failure and file recovery in A Bullet for Buñuel, where you include these screenshots of the file recovery software and things like that. So I wonder, how do you think about presentation, packaging, and distribution?

RM: The bite marks project was built around resourcefulness and the idea of embodying a value system, to disrupt relationships between “high” and “low.” It was the first project where I felt I could say I was an artist. I’d been making record sleeves since 1996 but I never really knew what I was. I’d also worked for seven years to make a 6.5 metres-long demountable portable plywood museum and its contents, which was shown in 2004, then defaulted back to books and zines as the most accessible form of exhibition. I was making a series of photographs of pieces of paper I had been biting into since 2005, and showed the original works at No.12 Gallery in Tokyo with a book of the project published by Nieves in Zürich. The idea was to reduce the time between the impetus and output of a work into a single moment, using what was immediately available, my mouth as a printing press and bits of paper. Within this idea it was possible to make a series of unique instantaneous performative prints with no studio, no materials, no resources, no training, no machines, no time, resulting in a series of very ephemeral relics of their impetus. I made a very overly elaborate box to house the complete works and resolve the project in 2018.

Bite Marks in Paper, 2005-2007

[detail view]

Bite Marks in Paper Archive, 2005-2018

[detail view]

BD: This is maybe one of the things that we have in common, working against the way that things are supposed to be used, using mediums against themselves. Your Obstacles series kind of summarizes that. You're setting problems for yourself or putting things in your own path that make you do crazy things to solve them.

RM: The Obstacles project builds upon an idea of throwing a spanner into my own works. There were patterns with long term projects, the Buñuel project, and others, that became encapsulated either in book form or as archive projects in the end. Each began with a specific narrative or point of research as a form of scaffolding, or skeleton, to build poetic structures around, which should be able to function on their own if the original impetus were removed.

I eventually met Luis Buñuel’s son, Rafael in LA and showed him A Bullet for Buñuel after years of working on it. We met in his garden and I was nervous to finally share the work he had been supportive of. After I showed him, he kind of went quiet and said, “This really has got nothing to do with my father, does it?” I was like, “No, not really.” And he goes, “He’d love it!” It was such a nice grasp and validation of what I’d been doing for so many years.

The Obstacles were a deliberate development on these kinds of precarious, long term projects that were sometimes expensive, often without any support, resources, or tangible reward for years afterwards. I had to rethink the idea of scale and figure out a system for making works that could sprawl incrementally and indefinitely in a way that still felt ambitious, but in a way that I wouldn’t continue to damage myself doing once our daughter was born. The Obstacle series was a way to disrupt my own tendencies. It was conceived as a generative system, to be able make work sequentially, with the scaffolding removed, that could continually scale, and not be contained.

Obstacle 79XR, 2022

Obstacle 79XR, 2022

Obstacle 83 Peripheral / Sentences Operating System, 2023

BD: When I saw you last you showed me your new Xerox prints and told me about your process of making those while your daughter is in ballet class. I’m really interested in the way necessity or “adhocism” dictates making. And then you were mentioning how they continue to unfold to you and potentially become three dimensional objects.

RM: My daughter was doing a summer ballet program, as she’s chosen to work really hard following her passion in pre-professional ballet training, so it’s an ongoing situation that I’m really proud of, and I’m working a lot while I’m at her ballet studio. During one particular summer ballet program I was working daily at the Morse Institute Library. I was using their photocopier to develop a series of visual text works, which use interrupted movement as a method to extrude small units of language into visual utterances. The photocopier was poorly maintained with a lot of toner residue in the mechanism, so it was adding unintentional broken lines and syncopated marks across the images. But with the history of Morse, the transmission of incremental visual language and sound, and notions of data storage and retrieval all having strong relationships with research and focuses within my practice, these signature vestiges of the Morse photocopier were perfectly in-keeping with the work. It was an incidental chance encounter that wasn’t repeatable, and a way to know that I'm in the right place at the right time in my life, and using the work as a way to navigate that. Honestly, it sounds a bit romantic, I hope it does, the practice of moving through the day-to-day and accessing what is already right in front of you, that’s really, really special. I think of it as my day-to-day job, maintaining that space.

Obstacle 89A Interrupted Thoughts, 2024-2025

BD: Paradoxically, it takes a lot of discipline to maintain an openness to that kind of thing. It’s much easier to fall into routine and close yourself off. I feel similarly, I go off studying these random subjects that seem to have no clear relation to anything I’m working on, or making, or any kind of larger project, but you have to have some kind of faith that that interest is going to take you someplace.

RM: I think you have to trust your body, you know what I mean? You think that you have to figure out the reason or motivation for picking up that material or process or being drawn to it, but the body also knows what it’s doing. I think you just find that through making work. The mind is a good starting point but at a certain moment the work has to move into the body. There is a reason and the reason will become clear at some point.

Ben DuVall is an artist and writer based in Brooklyn, NY, whose work synthesizes historical and conceptual research through drawings, oral histories, exhibitions, texts, billboards, websites, guided walks, radio broadcasts, books, and sculptural objects.

urtext.xyz